Struggling with mood swings, anxiety, or depression before your period and wondering if it’s more than just “PMS”? You’re not alone. In this episode of The Dr. Brighten Show, I sit down with Dr. Sarah Hill, trailblazing researcher and author of This Is Your Brain on Birth Control and The Period Brain, to uncover the hidden symptoms of PMDD and PMS that most doctors miss. We dive deep into how hormones shape your brain, why birth control may not be the fix you think it is, and the groundbreaking science behind progesterone, progestins, and your mental health.

This conversation reveals the truth about hormone sensitivity, trauma, neurodivergence, and perimenopause, offering insights that could transform the way you understand your body and your brain.

Symptoms of PMDD and PMS: What You’ll Learn in This Episode

- Why almost 70% of women with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder report worsening symptoms before their period.

- How progesterone’s metabolite, allopregnanolone, acts like a superhero for your brain and why progestins can’t do the same.

- The shocking reason why teen girls on birth control have up to 6x higher suicide risk than peers who don’t use it.

- The truth behind the phrase “Franken-hormones” and why synthetic progestins act more like testosterone than progesterone.

- How the HPA axis (your stress system) is disrupted by hormonal birth control and why this blunts your ability to cope with stress.

- Why perimenopause is the most dangerous time for women’s mental health, including peak rates of anxiety and suicide.

- The surprising research showing women choose sexier outfits around ovulation and what this says about your brain’s natural cycles.

- Why ovulation isn’t “optional” and how suppressing it robs your body of critical brain-protective hormones.

- The role of trauma and high ACE scores in increasing risk for PMDD and how it rewires the stress response.

- What studies reveal about the link between neurodivergence (ADHD, autism) and PMDD, with nearly 90% of autistic women reporting symptoms.

- Why the “bikini medicine” model of research has left women without answers for decades and what needs to change.

- Treatments that can help: from SSRIs dosed only in the luteal phase, to lifestyle interventions like exercise, vagus nerve stimulation, and saffron.

Diving Deeper into Symptoms of PMDD and PMS

PMDD isn’t just “bad PMS.” It’s a debilitating condition tied to hormonal sensitivity, not necessarily hormone levels. In this episode, Dr. Sarah Hill explains how changes in progesterone and estrogen reshape your brain each month—sometimes making you feel powerful and radiant, and other times sending you into a spiral of anxiety or despair. We break down:

- How estrogen acts like miracle grow in the brain, boosting sensory awareness and even attraction cues.

- Why the brain’s GABA receptors struggle to adapt in women with PMDD, making hormonal shifts feel like “falling off a cliff.”

- The difference between PMS and PMDD, including suicidal ideation as a defining feature.

- Why progesterone therapy can be life-changing in perimenopause, yet so few doctors prescribe it.

- The gaps in women’s health research, where women are often only studied in the first 9 days of the cycle to “make them more like men.”

This episode will help you connect the dots between your cycle, your brain, and your mood, while offering actionable ways to navigate PMDD and PMS with science-backed strategies.

About the Guest:

Dr. Sarah E. Hill is an award-winning researcher, professor, and bestselling author whose work is transforming how we understand women’s brains and hormones. With over 100 scientific publications, she is the author of This Is Your Brain on Birth Control and The Period Brain. Dr. Hill’s groundbreaking research uncovers how hormones shape mood, behavior, and mental health across a woman’s lifespan, making her one of today’s leading voices in women’s health and psychology. Her work has been featured in outlets like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Time Magazine, establishing her as a trusted authority on the science of women’s health.

This Episode Is Brought to You By

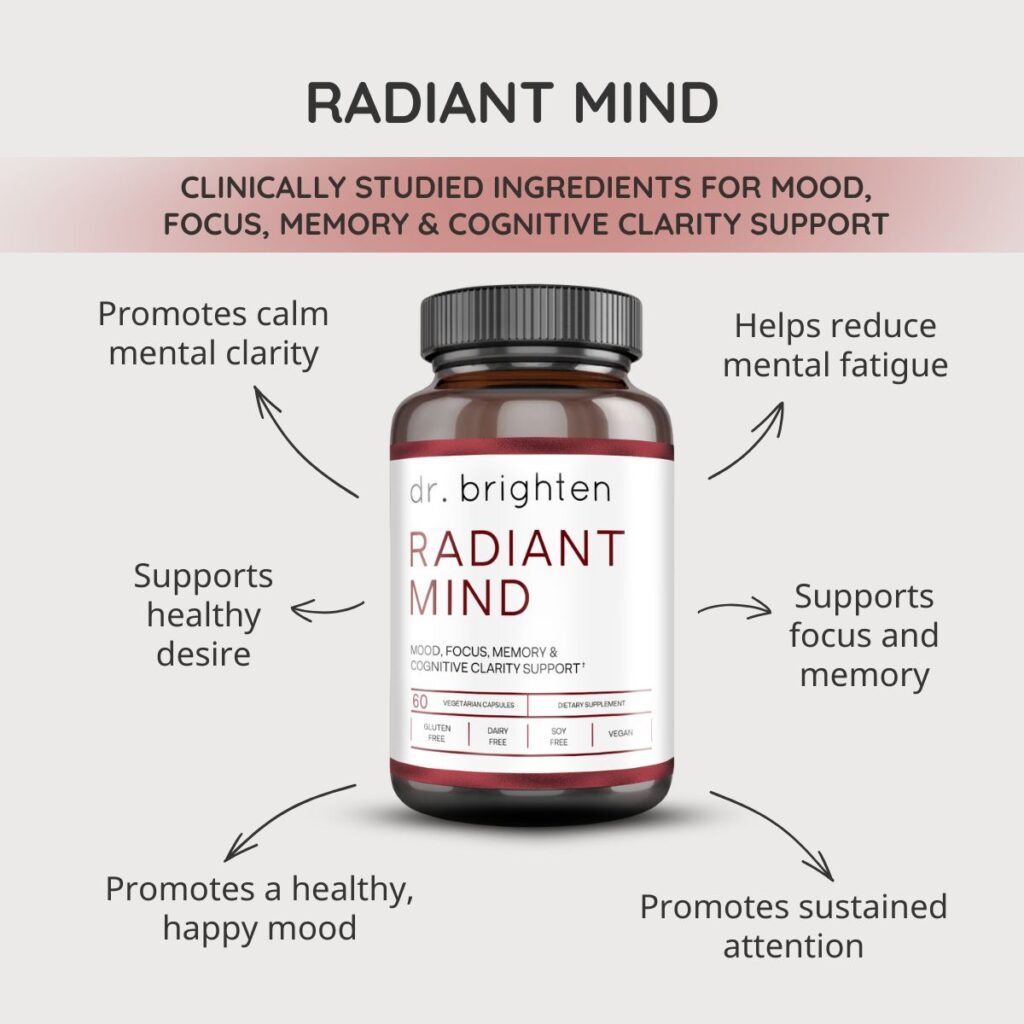

Dr. Brighten Essentials Radiant Mind—a science-backed formula created to support women’s brain health through every stage of life. If you’ve ever felt the brain fog of perimenopause or noticed how ADHD can amplify challenges with focus, memory, mood, or sleep, you’re not alone. Radiant Mind combines clinically studied saffron extract, Bacognize® Bacopa, Cognizin® Citicoline, and zinc to help nourish your brain chemistry and support clarity, calm, and resilience. And for a limited time, when you order Radiant Mind, you’ll also receive a free bottle of our best-selling Magnesium Plus—the perfect partner for restorative sleep and steady mood. Learn more at drbrighten.com/radiant.

Sunlighten Saunas

Want a gentle, science-forward way to sweat, recover, and unwind? At Sunlighten, infrared saunas deliver soothing heat that supports relaxation, muscle recovery, and deep, comfortable sweating—without the stifling temps of traditional saunas. With low-EMF tech and options for near, mid, and far infrared, you get a calm, restorative session tailored to your goals.

Exclusive for podcast listeners: use the code DRBRIGHTEN to save up to $1,400 on your sauna

Links Mentioned in This Episode

- This Is Your Brain on Birth Control by Dr. Sarah Hill

- The Period Brain by Dr. Sarah Hill

- Guide to Treating PMDD (Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder) A practical guide to understanding PMDD and the most effective strategies to find relief.

- Histamine and PMDD: The Hidden Link Worsening Your Symptoms Discover how histamine intolerance may secretly intensify PMDD symptoms and what to do about it.

- ADHD and PMDD Hormone Connection Learn how ADHD and PMDD intersect, and why hormones make symptoms so much harder to manage.

- Progesterone Intolerance: Symptoms, Causes & What To Do About It Unpack the real reasons behind progesterone intolerance and how to ease the side effects.

- PMDD in Autistic Women: Symptoms, Causes & Effective Solutions Explore why autistic women are more likely to experience PMDD and solutions that can help.

- How Hormones Affect Mood Throughout Your Menstrual Cycle See how monthly hormone shifts change your mood, focus, and energy—and how to work with them.

- Sleep Problems Before and During Your Period Find out why your period disrupts sleep and the science-backed steps to get deeper rest.

- Skovlund CW, Mørch LS, Kessing LV, Lidegaard Ø. Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1;73(11):1154-1162. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2387. Erratum in: JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jul 1;74(7):764. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1446. PMID: 27680324.

- Hantsoo L, et al., The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in depression across the female reproductive lifecycle: current knowledge and future directions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Dec 12;14:1295261. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1295261. PMID: 38149098; PMCID: PMC10750128.

- Rajabi F, Rahimi M, Sharbafchizadeh MR, Tarrahi MJ. Saffron for the Management of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv Biomed Res. 2020 Oct 30;9:60. doi: 10.4103/abr.abr_49_20. PMID: 33457343; PMCID: PMC7792881.

Other Episodes Not to Miss

- Unlocking the Power of the Menstrual Cycle: Hormone Health, PMDD & Period Care | Ashley Greene Discover how understanding your menstrual cycle can transform hormone health, period care, and even PMDD.

- Progesterone Side Effects & Intolerance: Why You Feel Worse on Progesterone| Dr. Jolene Brighten Learn why some women feel worse on progesterone and how to tell if you’re dealing with progesterone intolerance.

- Feel Sick Before Your Period? It Might Be Menstrual Flu and You Can Fix It | Dr. Jolene Brighten Unpack the surprising reason you feel flu-like before your period and what you can do to fix menstrual flu.

- How to Sleep Better by Fixing Blood Sugar and Sleep Disruptors | Dr. Jolene Brighten Explore how blood sugar crashes and hidden disruptors wreck your sleep—and how to finally rest better.

- Top AuDHD Expert: Shocking Risks of Undiagnosed Female ADHD & Autism | Dr. Samantha Hiew Hear the truth about the hidden risks of undiagnosed ADHD and autism in women, and why so many are missed.

- Menopause Brain Fog Is Real: 7 Science-Backed Ways To Clear It | Dr. Jolene Brighten Find out why menopause brain fog happens and 7 proven strategies to sharpen focus and memory.

- Side Effects of Stopping The Birth Control Pill: How to Stop Mood Swings, Acne & More | Dr. Jolene Brighten Get the inside scoop on what really happens when you stop the pill and how to smooth the transition.

- The Medical System Is Misleading Women About Symptoms of Menopause | Dr. Tara Scott Discover the myths and misinformation around menopause symptoms and what women really need to know.

- ADHD Burnout? Your Hormones Might Be Sabotaging You Uncover how shifting hormones fuel ADHD burnout and what to do to reclaim your energy and focus.

FAQ: Symptoms of PMDD and Treatment

What are the early symptoms of PMDD?

Early symptoms of PMDD often look like PMS but are more severe. They can include mood swings, anxiety, irritability, fatigue, food cravings, and difficulty concentrating that begin in the luteal phase (the two weeks before your period) and resolve once bleeding starts.

Can nutritional supplements support women experiencing PMDD symptoms?

While supplements are not a treatment or cure for PMDD, many women find that supporting their overall brain and hormone health can make a difference in how they feel. Nutrients like saffron, bacopa, citicoline, and zinc — the ingredients in Radiant Mind from Dr. Brighten Essentials — are researched for their role in supporting mood, focus, and concentration. By nourishing the brain and promoting calm clarity, supplements like Radiant Mind may be a helpful part of a comprehensive self-care plan that also includes sleep, nutrition, movement, and professional medical guidance.

How can you tell the difference between PMS and PMDD?

While PMS may cause mild mood and physical changes, PMDD includes debilitating mood symptoms such as intense sadness, rage, or even suicidal thoughts. PMDD interferes with daily life, work, and relationships, whereas PMS is usually manageable.

Is saffron helpful for PMDD symptoms?

Research suggests saffron may play a role in supporting mood and emotional well-being, which can be especially valuable during the luteal phase when PMDD symptoms appear. In a randomized controlled trial, women with premenstrual complaints who took 30 mg of saffron daily experienced significant improvements in mood compared to placebo. The researchers of this study concluded, “based on the findings of this study, saffron was an efficacious herbal agent for the treatment of PMDD with minimal adverse effects”.

Additional studies have also shown saffron to be supportive for stress resilience and emotional balance.

While saffron is not a treatment or cure for PMDD, it may be a helpful part of a broader self-care strategy. Radiant Mind by Dr. Brighten Essentials includes saffron extract (affron®), alongside bacopa, citicoline, and zinc, to provide nutritional support for mood, focus, and concentration. For women navigating cyclical mood changes, formulations like Radiant Mind can complement lifestyle practices such as exercise, sleep optimization, and stress management, always in consultation with a healthcare provider.

Can birth control pills cause or worsen PMDD?

Research shows that for some women, hormonal birth control can blunt the stress response and increase risks of depression or anxiety. In adolescents, studies found a six-fold increase in suicide risk among those using the pill. While some women find birth control helps, others experience worsening PMDD symptoms.

What treatments are available for PMDD?

Treatment depends on individual hormone sensitivity. Options include:

- SSRIs, sometimes taken only during the luteal phase

- Bioidentical progesterone therapy

- Lifestyle approaches such as exercise, improved sleep, vagus nerve stimulation, and saffron supplementation

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and neurofeedback

Is PMDD linked to neurodivergence or trauma?

Yes. Studies suggest nearly 90% of autistic women and almost half of women with ADHD report PMDD. A history of trauma or high ACE (adverse childhood experience) scores also increases risk by disrupting the stress system and hormone sensitivity. See the episode links for resources specific to this.

Does progesterone therapy help with PMDD?

For some women, yes. Progesterone and its metabolite allopregnanolone support calm, resilience, and neuroplasticity in the brain. Unlike synthetic progestins, bioidentical progesterone can restore the soothing, GABA-supporting effects that are often missing in PMDD.

Transcript

[00:00:00] Perimenopause is a time when most women get worsening of everything. PMS has been used to describe even minor experiences that we have. PMDD is more serious. It's generally a suicidal ideation. Women who've been through traumatic events do have a greater risk of developing PMDD, and it's pretty significant.

Studies show that almost 70% of women with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder experience exacerbation premenstrually.

It usually takes women a very long time to get A-P-M-D-D diagnosis. Those things may resolve and feel better once you're in full menopause. When you're in this state of hormonal transition, things can get a whole lot worse.

Dr. Sarah E. Hill.

Is a trailblazing researcher, award-winning professor and bestselling author uncovering how women's hormones shape their brains bodies and lives

with over 100 scientific publications and viral books. Like this Is Your Brain on Birth Control and the upcoming The Period Brain. Dr. Hill is transforming the way we understand female [00:01:00] health, one breakthrough at a time.

We're wondering why they're leaving their career. They regret being a mom. We just took a really hard time and we just threw

gasoline on that. It causes all kinds of changes throughout the body outside of the uterus. People almost don't wanna listen to it because it just seems to very fairy. What we find is that there is a greater risk of being.

Welcome to the Dr. Brighten Show, where we burn the BS in women's health to the ground. I'm your host, Dr. Jolene Brighten, and if you've ever been dismissed, told your symptoms are normal or just in your head or been told just to deal with it, this show is for you. And if while listening to this, you decide you like this kind of content, I invite you to head over to dr Brighten.com where you'll find free guides, twice weekly podcast releases, and a ton of resources to support you on your journey.

Let's dive in. We are gonna spend a lot of time in the luteal phase today. I'm so excited. We're gonna talk about P-M-S-P-M-D-D, what's going on with [00:02:00] progesterone, allopregnanolone, all of the things. But in your new book, you said something interesting and it was a study I hadn't seen before, and that is women during their ovulatory phase select sexier outfits.

In fact, like they actually drew like these ideal outfits and they were definitely sexier. Why do you think that's important for women to know?

I think that it's important to know that, you know, throughout the cycle, your brain is essentially guiding you down two different paths, right? And this is because for a woman to reproduce, there's two different jobs that her body needs to do, right?

She has to pick a mate and um, and find a mate, and attract a mate and have sex with that mate, right? So that's job one. Mm-hmm. And then job two is implantation. So allowing an embryo to implant and then for pregnancy to occur. And so understanding that our body and our brain is. Sort of all gearing up and, and acting in a way that is consistent with each of these two goals, I think is really interesting and important for women to understand because it's like, [00:03:00] it can really help us understand ourselves.

And indeed in that study, what they found is that in, uh, during the, you know, first 14 days of the cycle, we'll just roughly call that, you know, the follicular phase, but especially ramping up toward ovulation. So in that five days or so prior to ovulation, um, that women as estrogen is rising, that they become increasingly, almost exhibitionist.

Mm-hmm. Like women feel sexier. Yeah. You know, they're, they're selecting sexier clothes. And I think that that's really important a just to understand yourself, right. And understand what happens across the cycle, but also in some ways to understand what can happen when your hormones are suppressed. And, you know, of course, you and I have a shared interest in the birth control pill and the research on the birth control pill.

And just to veer really quickly into this. One of the things, and I didn't write about this in my, in my book about the birth control pill, but one of my own experiences that I had when I went off of it was I had that experience of having that increase in estrogen. Mm-hmm. And having that feeling of, you [00:04:00] know, like, wow, like I feel really good in my skin and I just feel sexy and like I wanna be out there in the world.

And I was missing that. And then when I went off the pill, you know, 'cause I was on it for 10 years and when I went off of it, I had that experience of feeling like, hello world. Yeah. You know, and it's like such a wonderful feeling and to feel that good about yourself and to have that kind of body positivity.

Um, and I think that this is something that women really do experience, you know, peri ovulatory and the research suggests that this is the case. And, um, yeah, it really just helps us understand ourselves.

Mm-hmm. We're gonna circle back, we're gonna talk more about the pill today For sure. 'cause I think it's really important in the context of P-M-D-D-P-M-S.

Mm-hmm. We know it's one of the top, uh, prescribed hormones. Uh, you know, across the board, right? Um, you and I actually had dinner last night and I had said to you, do you find it crazy that we are told our entire lives that the birth control pill is safe? But as soon as we get to menopause, we are told that these bioidentical hormones are suddenly dangerous.

Yeah. As [00:05:00] we talked about last night, I mean, there's. So many double standards in the world of women's healthcare. Mm-hmm. And this to me is one of them. And, and I think it's one of the, the key ones, this idea that giving women these synthetic hormones is somehow better for them than giving women who are in perimenopause and menopause, biologically identical hormones is just absolutely ludicrous.

And it's not supported by the data. Mm-hmm. I mean, the data support, the idea that for most women, hormone therapy is safe. Right. And obviously there are exceptions to this, but like by and large, and particularly when we're talking about biologically identical hormones, and you know, like one of my biggest pet peeves, and I'm sure that you've had this as well, are you gonna go to Progestin?

Yes.

I tried

nuts. So crazy about it is like, not only there, the confusion in practitioners where they don't quite understand the difference between these things, um, but the way that it's written about in the literature. Yeah. You'll have a study where they're giving women birth control pills or they're giving them progestin and then they're writing about it as progesterone.

Yeah. And so we [00:06:00] wonder why there's all this confusion in the literature about whether hormone therapy is safe or whether it's not safe. And it's because even the researchers themselves don't always know what they're doing. Mm-hmm. And like what they're describing. And it's really frustrating and I think that it's made a lot of women, um, unnecessarily afraid of hormone therapy.

Yeah. And a lot

of these women are women who would really benefit from it.

Yeah. As we were talking last night, I'm like, we should have recorded our conversation for you guys, but I was telling you about how like, um, going through IVF, this was just a few years ago, I went back on the pill. Within five days, I'm like the worst human ever.

And I'm gaslighting myself being like, this onset of mood symptoms cannot be this quick. It won't be this rapid. And my husband's like, no, you're either crying or you're yelling at us like what is happening? And then fast forward with endometriosis treatment. I was also given a round of progestin and I was.

You know, asking my doctor like, why not progesterone? And he's like, no, I wanna try this because this is what the research supports. Again, I was not a pleasant person, but when I take progesterone, as I was telling you, like I love [00:07:00] life, it's so good. My toddler cannot get on my nerves. Like it's fantastic.

So we see, especially ob gyn. Really we'll fight, like on the internet about how like, no progestin is the same as progesterone and there's no evidence that there's a difference. What does the research actually say? 'cause

they ain't reading it. Uh, no, I mean, that's just so crazy. It just makes my mind, you know, go like, what?

Because I mean particularly, you know, this is true when we look at the brain. Mm-hmm. And so just to like, back up on this, you know, progesterone is this like really beautiful hormone and it's really gotten a bad rap. And I think one of the big reasons it's gotten a bad rap is that people conflate it and, and sort of assume that it's the same as a progestin.

Mm-hmm. But the two things are very different Molecularly. So progestins, the majority of them are synthesized from testosterone. Yeah. Right? And so the, the chemists, the monkey with the, the molecules in a way where it does stimulate progesterone receptors. Right. And [00:08:00] so it will, you know, shut down ovulation in the brain.

So it tells the hypothalamus, like enough progesterone receptors are being stimulated, um, to, uh, to actually shut down ovulation, right? Mm-hmm. And to prevent the, the cascade that leads to ovulation, but it also stimulates a bunch of other stuff because it's a molecular weirdo. I mean, it's a Franken hormone.

It's such a molecular weird, it's, it's a Franken hormone. Yeah. No, it's a, it's a, it's, it's, it's like been pieced together in a lab. Yeah. And so it'll stimulate progesterone receptors and it doesn't even have great binding affinity, meaning that a lot of times it'll stimulate them and then fall off and then it will stimulate other receptors.

And so we know, for example, from research that it will stimulate glucocorticoid receptors, which is what picks up cortisol. Mm-hmm. Right? And so it can lead your body to go in a complete stress overdrive situation. And it can stimulate testosterone receptors, which is why women sometimes will end up with acne and facial hair.

Yeah. Depending on how androgenic their progestin is. And so pro. Skin is, has more in common with testosterone mm-hmm. Than does [00:09:00] progesterone. And most importantly, like to me, you know, everybody assumes that it's like, like a hormone is a hormone is a hormone, but like part of what makes progesterone so magical is what happens when it's broken down in the body.

Mm-hmm. And it's those metabolites that get released when progesterone is, is, um, is metabolized. And one of the things that you had already mentioned is this, is this like really beautiful neurosteroid called Allopregnanolone. And Allopregnanolone is, um, is only released from the breakdown of progesterone.

It is not released from the breakdown of progestin. Mm-hmm. Because they're just molecularly different products. And Allopregnanolone is like a superhero in the world of women's mental health. Yeah. And people don't know this. They don't know that they're missing out on this really beautiful product that our brain benefits so much from.

And the reason our brain benefits so much from Allopregnanolone is that it's. Stimulates GABAergic activity in the brain. And that's a really ugly word. I [00:10:00] hate the word GABAergic. Um, but it's stimulating your GABA receptors in your brain. And, and GABA is the primary, um, inhibitory neurotransmitter that our brain uses to calm itself down.

Mm-hmm. Right. And so for people who aren't familiar with gaba, um, it is what is released in high quantities when you're doing things like meditating, when you're doing yoga, when you put on your PJ pants and sit in front of the fire and you feel that really calm, relaxing feeling. Mm-hmm. And that feeling that you were talking about when you were taking progesterone where you just kind of feel a kumbaya.

Yeah. And that is like things kind of roll off your back. That's allopregnanolone. That is, um, that is your GABA receptors being stimulated. It's calming your brain down. It also produces, um, it increases neuroplasticity. Mm-hmm. It prevents over excitation in neurons in the brain. And so it has a lot of these really protective benefits to the brain and it also helps, um, increase.

Um, sort of, um, our, our brain's ability to adapt to things by increasing neuroplasticity. Mm-hmm. And so it's this [00:11:00] really beautiful hormone that's found to do things like help regulate our moods. Um, it helps to regulate stress. It has all of these really beautiful effects. You don't get that with progestin.

Yeah.

And what happens is, is especially, you know, if women are not ovulating and producing their own progesterone, they're not getting all of these benefits. Mm-hmm. Right? Because they're never getting exposure to actual progesterone. And so they're feeling. Anxious and stressed out and they're not able to regulate their stress response and their mental health is in the toilet and they can't understand why they can't calm down.

It's 'cause they're not getting enough GABAergic activity in their brain. Mm-hmm. Right. And they're not getting the effects of this really beautiful, wonderful hormone. And when you think about the idea of putting perimenopausal women or like, you know, who, who are already anxious and stressed out on, on something that's going to just further stress them out by diminishing any levels of allopregnanolone that they're actually producing from their little minimal amounts of progesterone that their body is producing while they're [00:12:00] still actually having active cycles.

It's all ludicrous. It's a recipe for poor mental health. Mm-hmm. And that's what we're doing.

Yeah. It's interesting because when it comes to perimenopausal women, we do see this increase of anxiety and depression. I mean it is a peak suicide rate, life, life cycle right there. Like, and that is so serious.

And what's interesting is that we've seen the research. It's the loss of progesterone diminishing in early perimenopause, the loss of allopregnanolone that is leading to this HPA dysregulation, and then you put them on something like the birth control pill, which is blunting cortisol response, which is further aggravating that whole, and for people listening, hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis, that's the HPA axis, your stress system.

And we're wondering why divorce rates are going up. People are like falling out of love with their life. They're leaving their career. They regret being a mom. It's because like we just took a really hard time of, of someone's [00:13:00] life and we just threw gasoline on that. We just said, let's amplify that. I wanna ask you because there is such a habit.

To put a teenage girl on the pill and just say, just take it for the rest of your life. Like until you wanna have kids or until you're through menopause, like, don't worry about it. Do we actually have any long-term data on what happens when you put a teen on the pill and she essentially doesn't get exposed to progesterone across her lifetime?

Yeah, that's a really great question, and unfortunately, like this is one of these questions that science has. Barely answered. Mm-hmm. Um, because of, I've got a whole soapbox I could get on about teenagers and I'm just not going to, again, and I have teenagers, so I'm like particularly sensitive to, um, how vulnerable they are.

Mm-hmm. Because here they are in this process where their brain is, is completely transforming itself Yeah. From a child brain to a grownup brain. And so their brains are so sensitive and we just treat them like little adults. Mm-hmm. Because they look like grownups, but their brains are still [00:14:00] remodeling themselves.

And so there's so much research that's lacking on teenagers and just about everything. And I think that they're a really grossly understudied group. Mm-hmm. And I think that we need to be more careful with them. So with that sort of soap box aside with birth control, you know, again, here's your brain going through this big remodeling project and like the lead architect in that remodeling project.

Sex hormones. Mm-hmm. Right. Sex hormones, puberty, we all know the story. And, uh, they play an important role in guiding appropriate brain development. And very few researchers have thought to ask the question of what happens then when you put women on the pill? These young women whose brains are still developing and are relying on their sex hormones to guide appropriate brain development.

Yeah. And including allopregnanolone and some of these other things that, um, play an important role in things like neuroplasticity and, and just even the, the, the ability of the brain to learn to regulate our hormones, right. So that our brain getting comfortable with communicating with our ovaries. Right.

That takes a long time. Which is why girls periods are [00:15:00] so wonky the first couple of years that they're cycling. 'cause their brain and their ovaries are still learning their, they're figuring each other out. Yeah. And learning how to regulate themselves. And so stopping all of that, um, from the little research that exists does seem to be linked with some long-term effects.

And so there's been research now using both mouse models and looking at longitudinal studies in humans that have found that. If girls or adolescent mice, um, are using hormonal birth control during, um, in, in the way that they usually characterize adolescents is like 12 to 19. Mm-hmm. So if women are on it between the ages of 12 to 19, um, and then they look at their risk of developing different types of, um, mood disorders over the course of their lifetime.

What the research finds in mice is that you get a long-term risk of anxiety like behavior. Yeah. Right. Because we can't ask the mice whether they're sad or anxious, but we see that there's greater anxiety like behavior even after they've gone off of, even after they've stopped administering the birth control pill.

And in humans, what we find is [00:16:00] that girls, adolescent girls who've been on hormonal birth control during that time are at a greater risk of developing major depressive disorder throughout their lifetime. After they discontinue the pill.

Mm-hmm.

Right. And this is serious. I mean, it's like, I don't think that, um, you know, and, and of course I've got teens.

Yeah. And, um, and you know, most people, like when their adolescent is put on the pill, it's not for regulating fertility. Right. It's for things like acne or, you know, having irregular cycles, which again, is so normal for the first couple of years of cycling. Yeah. And just really trying to find ways to help girls cope with that instead of trying to mask it mm-hmm.

Is really the best thing that we can do. But a lot of times girls are put on the pill and then parents aren't told, because a lot of times the doctors aren't familiar with any of this research. Yeah. That, you know, hey, just so you know, like, you know, this form of acne regulation that we're like, we're gonna try to help your teens acne, but oh yeah, this is going to put them on the road for developing major depressive disorder as an adult.

Mm-hmm. I think most parents and most children would [00:17:00] say, no thank you. Like, why don't we try something else? Yeah, like maybe I'll clean up my diet a little bit. But that's not what's happening because this risk isn't being communicated to women. It's not being communicated to girls. It's not being communicated to families.

Yeah. It's so important that you bring this up and I think people automatically, when we have these conversations, they're like, you must be antibi control. You must not wanna anyone to have access to it. And yet what you're advocating for is informed consent. Why is the birth control pill the only medication that gets a free pass where a woman doesn't have to be informed?

A lot of it is because of this, basically treating women at any age like their children and doctor knows best, daddy knows best. Like you. Just take your pill and be thankful that you have access to it, and I think that's really problematic. And it's, you know, I, I wanna say that when I brought up then the on the pill in my book that like, what I observed clinically is that women who developed mood symptoms when they were on the pill didn't come off and the mood symptoms just went away, right?

Like, it didn't, it didn't happen. [00:18:00] And there were so many clinicians were like, that's not true. I've never seen that, and I'm like, well, how many SSRI prescriptions are you doling out? Right? Like, have you stopped to ask yourself about this road of birth control to SSRI? Like we, we see this phenomenon happens,

right?

Yeah. There was a really beautiful study that was done on the entire population of Denmark. Yeah. So we're talking about millions of women. What they find is that the risk of being prescribed in antidepressant goes up significantly after you get a birth control prescription. Mm-hmm. And they find this to be true even after you statistically control for like how many medications they've been prescribed otherwise.

So it's not just that people who get prescriptions written and take prescriptions are more likely to then take more prescriptions. Mm-hmm. Even after you statistically control for that, what we find is that there is a greater risk of being diagnosed with depression. There's greater risk of then having to subsequently go on an antidepressant after you begin hormonal birth control.

And this is especially true for our adolescents. When you look at the risk of developing, um, a depressive, uh, [00:19:00] disorder or mood disorder of any type, including anxiety disorder, um, the, the risk that from taking the pill, um, on teenagers is so much higher. Mm-hmm. It's twice as high as it is for, for an adult.

And so this is a really vulnerable population that we need to look out for. And I think that the su There was a, another really beautiful study done in Denmark that looked at the suicide risk. Yes. And I think that they found that it was something like six times higher in teenagers, um, who are on the pill relative to teenagers who are not on the pill.

And the, the increased risk was greater for adults, but not like that. I mean, the, the teens are a really vulnerable population. Again, it's 'cause their brain is so receptive to sex hormones at that time. Mm-hmm. You know, it's like that is what's leading the charge in the pubertal transition and transitioning their brain from, you know, a child brain to a grownup brain.

And when you think about. How different a child brain is to a grownup brain. I mean, there's so many differences. It's like you're a completely different person. [00:20:00] Yeah. And the idea that you're going to mask and like shut down the sex hormones that through for millions of years has been what has guided our brain development during that time.

Mm-hmm. Is ludicrous. It's nuts

that I believe that Denmark study was the 2016 study. I'll link to it in the show notes. I remember when that came out and how many women felt validated. Mm-hmm. They've been telling their doctor for years, like, I'm getting mood symptoms. And doctors are always like, well, there's no research to support that.

So it's just in your head. It can't be the birth control pill like you are broken. It's not a medication side effect. Right. And why are you trying to villainize the pill? I never understand this, like protecting the pill over protecting the patient, uh, mindset. But that study came out. So many doctors lined up across the internet to say that study was invalid.

It was a poor study. And women, you are still wrong. You're still making things up. And that was a moment that I just sat back and observed and I was like, this is a catalyst moment for the distrust women have for their providers. Now, women have been saying it for [00:21:00] years. Providers said, we need to study. We don't have a study.

There's not good enough research. Study comes out. They're like, no correlation's, not causation. Pass it off. And that was the moment that I think women really started to question their doctors birth control. They started to look at the generations before them, and now we see. Here we are almost a decade later and doctors are still like, oh, it's just influencers.

Villainizing the birth control pill that makes women not wanna use it. It is doctors being dishonest and gaslighting women that have made them not want to use it. And I think that not taking responsibility has landed us in a very serious situation in women's health. So we've been talking a lot about the pill, which is your first book.

Um, but you have your new book and I wanna talk more 'cause you go, um, more into PMDD talking about different aspects of what's going on with the HPA access and something that was interesting that when I was reading your book, so you know, I'm working on a book, so this I actually [00:22:00] wrote in my book, is that research has shown that cortisol hyporeactivity, which is like called blunted cortisol response in early puberty, is predictive of major depressive disorder.

So as I was, as I was reading your book, when I thought is like, we know the pill. May lead to a blunted cortisol response in some women. We also know teens using the pill are the greater risk for mood disorders. So I'd like to get your thoughts on this HPA issue, this cortisol hyporeactivity, and, uh, I was gonna go into like what uh, parents should know for their teens, but I feel like you covered that.

But it was just something that struck me is that I wrote this in my book about how, you know, seeing a disruption in the HP axis and the cortisol response early in puberty. Can co, can put you at risk for major depressive disorder. How does that relate to what the pill can do for your, for cortisol blunting?

Right. So we know, um, from research that, uh, if you go on the pill, and [00:23:00] this is particularly probably true in adolescents, I haven't seen it broken down this way, but generally what we tend to see is that you get a blunted cortisol response to stress as noted. And it's believed that this happens because again, these.

Progestins are Franken hormones. They bind to lots of different types of receptors, including glucocorticoid receptors, which pick up cortisol. And when the body is getting too much cortisol, it will just shut down the HPA axis. It'll say no more stress hormone for you. And the reason for this is that cortisol is a major mobilizer of resources in the body.

And so one of the things, you know, we always tend to think about cortisol and stress, but cortisol just mobilizes, um, glucose and it mobilizes triglycerides and other things to help mobilize energy to our brain and to the rest of our body during times when things are consequential. Right. It's essentially a sign that this, this is meaningful.

Mm-hmm. Like what you're doing right now matters. Right. Whether it's running away from a bear Right. Or whether it's your wedding day. Right. It's saying this matters like pay attention, have all of your, have all boots [00:24:00] on the ground. Um, but that's really metabolically expensive. Yeah. When you have cortisol in the system, it's taking that glucose and triglycerides from doing other things.

Mm-hmm. Right? Because that would be used to do things like fuel, the immune risk. Bonds, right. And create, you know, cell cellular repair and all of the other jobs that our body has to do. And so cortisol is disruptive when it's, when it's, um, released for long periods of time. Yeah. Because it's essentially taking all these resources, having them circulating in the blood for the brain and the muscle tissue, and then our immune system isn't able to do what it's supposed to do.

Our cell, you know, our cell repair isn't able to do what it's supposed to do. And so our body will just say enough. Mm-hmm. You know, because it doesn't want the body to completely fall apart because that is what will happen. The reason that salmon fall apart after swimming upstream is because of cortisol release.

Yeah. Constant cortisol release literally makes the body fall apart, and so the body will just shut it down. If there's like chronic, um, exposure to glucocorticoids, it's like, alright, enough, no more stress for you. And then the, the, the system gets shut [00:25:00] down. And with the pill, when you have this, these progestins that are stimulating these cortisol receptors, it's making the brain and body think that it is in a, you know, a state of trauma.

Mm-hmm. Right? Like chronic exposure to stress. And so the body seems to be shutting it down. And this is consistent with what we tend to find with women on the pill because they have these really high levels of glucocorticoid binding globulins in their bloodstreams that are essentially the liver saying, no more cortisol for you.

Mm-hmm. Right. And this is the reason we get that blunting and that blunting. At first it might sound like, wow, that's great, then you don't experience stress. But of course that's not what happens. Yeah, that would be nice. But it's not the reality. Yeah. Yeah. Not the reality. Because cortisol is how we cope with stress.

Mm-hmm. It's how our body mobilizes resources so that way we can deal with things that are meaningful, again, whether bad or good. And so when you blunt that you're actually blunting your ability to recover from stress, you're blunting your ability to manage stress or blunting your ability to sort of move smoothly, move from situation to situation.

'cause cortisol [00:26:00] is part of how we adapt to our environment. Yeah. And so it minimizes your ability to adapt to the environment. And this of course can cause problems, right? This can cause problems with mood because when you aren't able to cope with your environment, I mean that causes anxiety, which ultimately leads to depression.

Right? It also can create issues with arm. Ability to cope with hormonal changes. Mm-hmm. And so one of the things that I write about in the, in the new book, the Period Brain, is I talk about the, you know, when we look at women who tend to suffer from really bad PMS and PMDD, many of them have a history of trauma or they have a history of, um, having blunted, uh, HPA access response.

Mm-hmm. And what seems to be happening when you look at all of the pieces together, the puzzle seems to be revealing a picture where these women aren't able to cope. They don't have what, what I refer to in the book as resilience. To hormonal changes. Yeah. Because when our hormones are going through rapid periods of change, our body and our [00:27:00] brain are going through rapid periods of change, and there's a lot of adaptation that has to go on.

Um, there has to be adaptation in terms of our hormone receptors, right? So receptors for things like estrogen or progesterone, but also, um, there has to be a lot of, um, plasticity in terms of things like our, our, um, GABA receptors. Because allopregnanolone levels for naturally cycling women mm-hmm. Are rising and falling during the second half of the cycle in ways, given that they stimulate GABA receptors in the brain.

Our brain has to be able to adjust to those things. Cortisol is the master coordinator of adjustment. Right. It's, it's saying mobilize resources to help us deal with this change. Right. We can think of it as a hormone that helps our body cope with change. Mm-hmm. Right? Because that's kind of one of the, the principle elements of stress and, and, and hormonal change is a form of stress.

Right. Because it's something that is an event that our body needs to cope with, and that's generally the way that we define stress. And so when you're lacking what I call like HPA access tone. Mm-hmm. Right? Like when you've got like a really [00:28:00] nice dynamic cortisol response, like when things are stressful, you get big cortisol release and when things are not, it goes back to normal.

Um, when you're lacking that and have that blunted response that we see in women who've experienced trauma or women who've been on hormonal birth control, um, this. Can diminish your ability to navigate smoothly between hormonal transitions and the luteal phase of the cycle that lasts two weeks of the cycle when you have this huge ebb and flow of the sex hormone, progesterone, right.

And the rise and fall of progesterone happens at levels that are 10 times higher than the rise and fall of estrogen. So even though we all see that little menstrual cycle map that shows this like big shift in estrogen in the first half of the cycle, and then this, you know, just slightly larger shift in progesterone, those things aren't drawn to scale.

Mm-hmm. And the y axis that's showing levels of progesterone is actually scaled at 10 times, um, 10 times higher than the estrogen side. And so we have this huge increase and huge [00:29:00] decrease in progesterone during the luteal phase. And you also get a big increase in decrease in estrogen mm-hmm. That many people don't really pay any attention to because they're always focused on the estrogen shift that happens in the first half of the cycle.

Yeah. Right. Prior to ovulation. And that's a lot of adjustment that our brain and the rest of our body is having to do to cope with that rise and fall of, of hormone. And, and again, it, this isn't just with our hormone receptors, it's with our GABA receptors in our brain because they're getting this. Big rise and fall in Allopregnanolone, and if you're not able to adjust to those changes quickly, it's gonna make you feel messed up.

Mm-hmm. Right. And what we tend to see is that a lot of women who experience PMDD, that's exactly what's happening when they've done studies. These are usually done using animal models and just looking at the, their ability of their neurons to um, like sort of increase and decrease GABA receptors as needed and modulate their GABA receptors in response to that rise and fall of Allopregnanolone.

And [00:30:00] it suggests that it's compromised mm-hmm. Right. In these women. And so they're not able to like, sort of gracefully navigate their way through the luteal phase. And the results of that is they feel absolutely terrible. Mm-hmm.

I wanna zoom out a bit, um, because you said like your brain's changing across the menstrual cycle, but something you, well, let me just say, I also appreciated that graph in your book.

'cause I think you had on there like arbitrary units of like how we always present the menstrual cycle and the way. As I we're having this conversation, like we always present it this way so that the patient can wrap their head around it. But I, as you're saying it, I'm like, I do think some clinicians have taken it as fact.

Yeah. Like they're like, fact, this is exactly what it looks like right now. In your book, you said estrogen acts like miracle grow in the brain. So tell us how that plays out in terms of brain function and behavior.

Yeah, so estrogen essentially primes your brain to be its most alert, sensitive self. Mm-hmm.

Right? And the reason for this is like, this is a period [00:31:00] in time when. Sex can lead to pregnancy and there is no better time for your brain to roll out the red carpet in terms of your sensory Yes. Acuity during than during this time because you're essentially choosing who your genes are going to be intermingling with mm-hmm.

In the next generation and future generations beyond that. And so the process of evolution by selection, this process that has shaped our brain and shaped us to be, you know, the way that we are as human beings, has shaped us to be incredibly sensitive to the environment, and particularly cues related to, uh, mate attraction, uh, during this time in our cycle.

And what we tend to see is that women are more alert, they're more energetic, and they get, um, new dendritic spines on their neurons. So their sensory for people who don't know what that is. Yeah, yeah. Can you explain it? Yeah. Yeah. So, so our neurons, if we always think about the brain as being this like lump, right?

Yes. We know. It's just like this lump and it's so like, and, and, and then it nothing does. Nothing changes, right? Yeah. We just think that it's this like lump and it [00:32:00] sort of is what it is. But that couldn't be further from the truth. The, the brain is just like this beautiful, it's a process. Mm-hmm. And it's always shifting based on the environment and the hormonal environment is one of those things that makes it shift.

And as our hormones change, um, you know, as estrogen is rising in the cycle, you get these little spines that pop out of neurons and they're there to be more sensitive to any information that's coming in. Mm-hmm. Right? So the more of those that are out, the more sensitive we are. And when they retract, the less sensitive that we are.

And the reason our brain isn't always rolling out the red carpet is that that's incredibly metabolically expensive to have all of these dtic spines that are like very aware of like even fine tune differences in scent and fine tune differences in appearance. And this is what we find in women when they're in the estrogenic phase of the cycle.

Particularly prior to ovulation, you get like, women are able to tell the difference between really small [00:33:00] differences in, um, things like cues, for example, related to testosterone. Yeah. So we find that when women are in the estrogenic phase of the cycle, they're better, better able to determine and notice what we just noticeable differences between, um, testosterone markers in men's faces.

Mm-hmm. Right. So for a woman in the luteal phase, when estrogen levels are lower and progesterone is high, they'll be like, they all look the same to me. You show that to a woman near peak fertility in the cycle, and she's like, that guy's different than that guy. That guy's different than that guy. And that one's hot and that one's not.

Yeah.

And you get this, these really interesting differences in just being able to detect these fine tuned differences. We also find this with scent. So they've done this looking at what a woman's sense sensory threshold is for picking up fine tuned differences in a metabolite of, uh, testosterone that's picked up in sent.

And women are more sensitive to that as well. And so it's like our brain is just primed for information and it's like, you know, wants to make good mating related choices. And so it's really sensitive to all of these different types of cues. So the brain [00:34:00] is primed for all of these cues because conception is possible.

Mm-hmm. And so estrogen does act like miracle grow in the brain. It just makes it, you know, this really sensitive, um, version of itself where it's very much aware of a lot of these fine tuned differences that are important in partner choice. And it ends up making us more sensitive to the world. And this is also why the seizure threshold, um, uh, becomes lower.

Yeah. Um, during, like right prior to ovulation is because our brain is so sensitive to sensory stimuli that it can become overwhelmed. Mm-hmm. Right? And that of course, um, can produce migraine headaches and it can produce seizures.

Yeah, everything you just pointed out, it's so controversial. Why is it so controversial to say that women are attracted to a certain type of man, especially if they're natural, naturally cycling versus birth control, that they can pick up on these scents?

Because whenever I talk about this, whenever you talk about it, I see people punching back hard, right? And they're like, stop reducing women to this and, and women select mates for we're, we're way more intelligent than that. And I'm [00:35:00] always like, at your core, you are an animal, right? Yeah. You just are an animal that has a language that you understand.

So you think you're unique, but you are an animal.

Right. Yeah, no. Part of that wisdom, 'cause we do have so much wisdom. We have millions of years of inherited wisdom on our shoulders, right? We have a brain that is the result of an uninterrupted chain of successful reproduction for millions of years, knows a soundbite right there.

It's so amazing. Well, it is. Well, I mean, think about this. If even one of your direct ancestors would've failed to be able to attract a mate. Reproduce and have a baby successfully, you would not be here. Mm-hmm. So each one of us is an evolutionary success story, and I think that's incredibly empowering.

We have this brilliant brain that has managed to get genes down from the, you know, generation to generation to generation for millions of years. It's brilliant. And so why do people have a problem with that? You know, I, I think that it's. [00:36:00] There's still this, but you know, and I think part of it is, you know, the field of medicine in particular was created before we understood that the Cartesian mind body split just wasn't true.

Yeah. You know, like where we used to think that the body was, you know, the sack of meat that followed these laws of, of biology and that the brain was a product of the soul and that it, it had its own sets of properties and that the two things shall never meet, but we know better now. Mm-hmm. We know that the brain is a body part.

It is governed by the same rules that govern the rest of the body. And so the idea that our brains are influenced by our hormones, it's just, I mean, it's biology 1 0 1. Mm-hmm. It would be impossible for them not to. Uh, and, and, and it's like the most important body part we have is our brain. And the idea that it would somehow be immune to our hormonal influences is completely cuckoo nuts because our hormones make us better.

They don't make us worse. And I think that there's also this like belief out there that. There's something [00:37:00] wrong with our hormones and that our hormones make us somebody other than who we are when it's like our hormones are who we are. I love that your eye

roll in that statement. I mean, it's like

they're, they're who we are, you know?

And, and in my first book, I have a chapter and I want, I wish I could write the same chapter in every book I write, but it's just you are your hormones. Yeah. You know, they're part of like the, the cr, the like what your brain uses to create the experience of who you are. So who you are is created by all of these gears and sprockets going on inside your brain that are influenced by, you know, neurochemicals and neuromodulators and neurotransmitters and electrical activity and hormones.

And that is this version of yourself that you've created in your head, and that's the version of yourself that creates behavior and makes you who you are in the world. We're so much better for it because our hormones help us adapt. Yeah. You know, we talked about cortisol and it's like when you don't have that, you're not able to adjust your behavior appropriately and

evolutionary speaking, you would've died.

Yeah, you would've died. You would've been like, as I escape the predator. Not ever. No, no, no, no. Yeah,

no. You'd just be chilling with your. [00:38:00] Friends, you know, when the saber tooth tiger's coming or you'd be chilling with your friends when there's a potential romantic partner that's high quality. 'cause another uh, domain in which cortisol just gets absolutely flooded in the body is attraction.

Mm-hmm. You know, so it's like we, you know, stress is, is, is a lot of different things. Right. It's just your body saying this is important. Right. This hasn't, this has consequences for your ability to survive or your ability to reproduce. Yeah. Pay attention, mobilize all the resources. Right. Pull up some of that energy that you're using to divide cells and, and deal with the, and deal with the immunological challenges.

Mm-hmm. And let's direct that to the brain right now because it needs to do whatever it needs, you know, to attract that mate or to get away from that saber-tooth tiger.

Yeah, and I think, you know what came up when we were talking at dinner last night and I had said to you like, I think that the women who came before us.

And we definitely see it's that boomer generation of gynecologists who I know. I'm like, is boomer a bad word? I don't know. But it's the generation that it is. I don't know, you guys can tell me in the comments, I don't mean that with disrespect, but is that generation of [00:39:00] gynecologists who were like, just suppress your hormones with birth control.

There's no reason that you need them. You can be just like a man and work just like a man. If you do that, don't ever acknowledge that our hormones make us different, make us act different, make us think different, make us do anything different. Like that is just, you know, crazy talk. And I get that they did that because they were like, we feel like we have to.

Tell men we're the same as them to be able to advance our careers. But I absolutely think they did tremendous harm in women's health. And I don't say that as like people, you know, in general, I'm talking about practitioners. Mm-hmm. Who were telling women that your hormones are something to be suppressed mm-hmm.

Ignored. Mm-hmm. And never acknowledged. Mm-hmm. Because they'll find a way to weaponize it and say, we're weaker, which. I have always said, your hormones give you superpowers. And I believe very much in everything you're just saying. It really demonstrates that they absolutely do give us superpowers. And the dynamic change across the cycle is something that when you understand, you can [00:40:00] absolutely leverage.

I wanna go into that, 'cause I feel like you've talked about like the changes with estrogen. What's going on in the follicular phase? We've kind of alluded to like, you know, the allopregnanolone, the GABA receptors, but can we just go across the menstrual cycle and kind of put it together for women, what's happening with their brain?

Right. Let's just talk about why we have two hormones instead of one. Mm-hmm. Right. And And as you noted, I mean, for a long time it was assumed that there must be something wrong. Yeah. With having two hormones instead of one because men have one there, right? They have one primary sex hormone. They have

like a very basic operating mode.

Right. Altogether. Right. And I don't mean that with disrespect people. I'm raising two boys, but like. They don't have to do anything fancy. Right. Right. 'cause they just have to ejaculate. Yeah. But we actually have to gest state, like Right. There's so much more going on.

Yeah. No, it's like our bodies have two jobs to do for reproduction.

Right. There's made attraction and sex and then there's implantation and pregnancy. Mm-hmm. And so it's like our, we have two hormones because our bodies and our brains have two different [00:41:00] jobs to do in order to pass down genes. Men have one. And the only reason that we think that that's better and superior is because men were studied first.

Yep. So all of our default assumptions about what it means to be a human and like a functioning human is based on a male typology. Mm-hmm. And that just doesn't work for women. And as you noted, it's like for a very long time, um, it was assumed that, yeah, there was something wrong with our way of being.

That's simply not true. And, you know, we could turn that argument on its head. And, you know, just to give you an example, you know, there's this idea that, oh, well women are fickle. Mm-hmm. Right? Because our hormones change and therefore, like, who are we? We could turn that on its head and say, men are overly simplistic.

Mm-hmm. You know, like if you can't look at things through two different lenses, then you're completely inefficient. You know, you're, you're, you're inept. But we've embodied Yeah. This idea of inferiority. And I think that that's what's guided this decision making where it's like, we need to suppress the discussion of [00:42:00] hormones and like, why they're important.

Because women have embodied this idea of inferiority that's simply not true. Hmm. You know, it's like our hormones are part of our wisdom, they're part of our bodily wisdom. When we tell women they don't matter, it makes them feel pathological.

Yes.

Right. And so part of this, my book is, you know, even though I think we've gotten more comfortable societally.

With the idea that women cycle, right? Everything is focused on estrogen. Right? And this is true, um, in popular discussion. So when we talk about like, oh, you know, hormones matter and you know, estrogen does this and estrogen does that, and estrogen does this. Um, and this is also true in research because, um, because men were studied first, um, the way that researchers decided to deal with women's hormonal cyclicity in research was to try to study women only when they're most like men.

Yeah. And so, I know, right? I just have to laugh when you say that. 'cause it's like, oh, thanks for including us in drug studies, but also not really including right. In our entirety.

[00:43:00] No. Yeah. So it, so one thing that, um, people aren't usually aware of is that in most biomedical research, women are only included as research participants during the first nine days of their menstrual cycle.

Mm-hmm. Right? And the idea is that they're trying to keep, they're trying to study women only when their hormone levels are maximally low, to make them maximally similar to men. The problem with this is, of course, is that women are not in that. Hormonal state most of the cycle.

Yeah.

Right. They never study us when hormones are high.

And so we have this whole other set of assumptions that our body is following when it's under progesterone that are never, ever studied. Right. So it's like we're we're studied. Um, they, they now include women in research, but they don't study us as women. Right. Because women are cyclical. Yeah. And so we have these two, we have these two primary sex hormones.

Estrogen, again, gets all of our gears working together for attraction and, um, and sex. And then progesterone gets all the gears working together for implantation and [00:44:00] pregnancy. And this doesn't sound like that big of a deal. Like, oh, okay, well, whatever. I don't care what that has to do with anything. Um, it has a lot to do with everything.

Mm-hmm. And the reason for this is that for pregnancy to occur. The female body has to absolutely change the rules of engagement for almost every system in the body. What our brain does has to differ, right? We have to become, for example, less interested in sensation seeking and wasting energy, going out and chasing opportunities because our energy levels are gonna be lower when we're pregnant, right?

So it actually dampens. Our, um, reward sensitivity to rewards in the environment. Right? It also lowers our threshold for when we see something as threatening, because women, when they're pregnant are in a more vulnerable state. They're not able to get away as quickly. And so we become more sensitive to threats, both social threats and physical threats.

Our immune system has to change what it's doing because our very inflammatory immune system that we have during the first half of the [00:45:00] cycle, and not inflammatory in a bad way, but just a very reactive immune system, estrogen is, is it helps to prime the immune system in a lot of ways. Mm-hmm. Um, and.

Progesterone has to tamp down the brakes on that because if you have a super active immune system and you have an embryo that's trying to implant, it looks a lot like a pathogen because it has genetic material that doesn't belong to self. And that's what the immune system will go after if it's in its heightened state.

And so it shifts our immune system from a, a, what, what we call a th one response to a th two type anti-inflammatory response. Our circulatory system has to change what it's doing because all of a sudden it has to have a lot more blood flow going to the uterine area. And this is something that happens in pregnancy, but also in pre-pregnancy.

In the luteal phase, our body temperature increases, which means that our, uh, basal metabolic rate has to increase. And so we see that women's calorie needs increase by about seven to 10% in the luteal phase of the cycle. Mm-hmm. Um, our respiration rate [00:46:00] and our heart rate increases, our respiratory drive increases, meaning that we feel the need to get breath more, so women feel more, um, out of breath when they're working out heavily during the second half of the cycle.

Our ability to build muscle mass decreases because our body is taking those energetic resources and is directing them toward building an endometrial layer. Mm-hmm. Everything. Changes. Yeah. Right. And so the idea that we can take rules that were created from science conducted on men and apply that to women doesn't work.

The idea that we can take research that was conducted on women in the early stages of the menstrual cycle when estrogen is the primary hormone, and then apply that to progesterone, that also doesn't work. Mm-hmm. Right? And so a lot of what we know about ourselves. Is, is completely guided from what is sort of normal for a woman during the estrogenic phase of the cycle.

And it doesn't necessarily apply to the luteal phase. And so I talk about this book and talk about this idea that, you know, when we think about [00:47:00] estrogen, everybody's like, oh yeah, you know, it, it does sort of make me wanna have sex more. And you know, and I feel sexier and it's doing all these things that promote sex, sex, sex.

And then there's the luteal phase, and that's just. PMs, I just feel terrible. And it's like, well no. Like this is actually, there's a lot of wisdom in these psychological and physical shifts that are going on. Mm-hmm. It's just that one, they've been made to feel pathological because we've been given a one size fits all version of what it means to be human.

That does not fit for a female. It just doesn't fit. If you're a cycling female that doesn't fit, you have two sizes. Right. There's at least two right versions of what your body needs and what it does. Mm-hmm. And when we're not told about that, it feels pathological. And the other part is that our body actually creates pathology.

'cause we're following guidance that was never created for the cycle phase. Yeah. You know, so for example, you know, one of the things I talk about in my book is this idea that. You know, all of us are told from nutritionists, here's the number of calories that you need to have on [00:48:00] a given day. Right? And here's how you need, you know, from your trainer, here's how you need to work out every day of the cycle.

And that might work well and good during the first half of the cycle. But then when you shift into the luteal phase and your calorie needs go up by seven to 10%, you know, if you're somebody who usually eats about 2000 calories a day, that's between like a, an additional 140 and 200 calories a day. Mm-hmm.

Women already told this. Yeah. Right. And instead they're like, God, you know, I'm so hungry. And then we start to tell ourselves a story, right? About how we have no self-control. What's wrong with me? Right? And then because you're hungry and your body, which thinks it's gearing up for a pregnancy, is gonna see this as an emergency, right?

So your hunger hormones are gonna be telling your brain emergency. And so then your brain is going to be like, oh my gosh. Like I, you know, and then you start having food cravings and the next thing you know, right? You're in the pantry eating peanut butter outta the jar. And then you're like, what did, like, why did I do that?

You know? Like, why did I do that? And it's because we didn't do what our body needed. Yeah. We didn't listen [00:49:00] to it. And as women, you know, and, and you, you talked about this early on in the inter interview, and I really appreciated this. Um, and especially from somebody who's been in the clinical world, it's like.

Our doctors have taught us to distrust our bodies. Yes. From, from the time we're small, you know, and, and this, there's no better example of, of what happens in the luteal phase, you know? And, and we experience these shifts, right? We're feeling hungrier and we're telling ourselves a story like I am, have no self-control.

I just suck. You know, I have, I'm never gonna, you know, I have no willpower. We tell ourselves these terrible stories about ourselves. Mm-hmm. We think that our body is the enemy when it's guiding us toward the things that we're actually supposed to be doing to take care of our bodies. But because that flies in the face of the bad advice that we've been given, we learn to distrust ourselves instead of distrusting our doctor or distrusting the nutritional advice that we've been given.

Mm-hmm. And it's time that we start really taking these things seriously because even though I [00:50:00] recognize that for a very long time, women were. Treated as inferior versions of men, just because we cycle, it's time that we totally shift that narrative and we embrace the fact that we cycle. Because when we don't do that, we go through these, you know, entire two weeks of our lives, um, every single month where we feel completely outta control and pathological.

Yeah. And like it's time that we really take that seriously. It's time that we understand it and then learn about ourselves during this phase in the cycle, which is what I'm trying to do with my book. The Period Brain is really educate women about what is your body actually doing during this time and what do we need to take care of it during this time?

But then we also need to use this to change science for the better because currently the gold standard in clinical research. In biomedical research is to only study women in the first nine days of their cycle. Mm-hmm. That's the gold standard. That's considered a really well done study, and that makes absolutely no sense whatsoever.

And this is why a lot of women experience premenstrual [00:51:00] worsening or premenstrual. And I say this because a lot of times when women experience premenstrual worsening of symptoms, it's during the last full two weeks of the cycle. Yeah. And we see premenstrual worsening of things like asthma, A DHD, which of course we talked a lot about.

Um, we talked a lot about yesterday. Um, you see premenstrual worsening of, um, eating disorders. You see premenstrual worsening of personality disorders. Of mood disorders. Mm-hmm. I mean, the list goes on and on and on and on. And women report that the drugs don't work as well during certain phases of the cycle compared to other, I mean, and, and.

That's just scratching the surface, you know, it's really, we need to be studying women under control of both of their primary sex hormones, not leaving progesterone in the ghetto, and as a result, leaving women in the health ghetto during this phase of the cycle.

Mm-hmm. This is so well said, and it's, as you're saying this, I'm like, you know, part of why you and I are considered so controversial in our work is because we're challenging an entire paradigm that has told women that they're inferior, but not just told them.

That [00:52:00] actually profited off of that, actually been able to, you know, basically put us in the corner so that other things can be advanced at our expense. As you were saying, these things that get worse before your period. I was actually surprised when I read in your book where you said that studies show that almost 70% hard explanation point right there of women with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder experience exacerbation the premenstrually.

So for people listening, everything's getting worse. Leading up to your period, and you know, in the case of PMDD, and we're gonna define PMDD and PMS in a second. When you consider that this is two weeks out of every month, that is half the year, in what world would we ever tell a man? It is okay for you to be debilitated and feel awful for six months out of the year and yet.

It is something that has been perpetuated in women, and I'm not saying this as if men [00:53:00] had it out for us in saying this, it is that medicine didn't care about us enough to study this. So wanna talk, I wanna shift gears to talking about PMDD. Let's define PMS versus PMDD. 'cause you talk a lot about this in your new book.

Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Yeah. So the difference between PMS and PMDD. So PMS, it describes almost everything that women experience in the luteal phase. Mm-hmm. You know, from really minor disturbances in just feeling more tired and sluggish, which is allopregnanolone actually stimulating your GABA receptors and making you try to conserve energy.

Um, because the luteal phase is so metabolically expensive because of all that new cell creation in the endometrial area. Not

to mention

immune

risky. Yes. You wanna, you wanna stay home more? Yeah.

No, exactly. Yes, yes. No. Yes. Brilliant. Yes. And so, um, PMS has been used to describe again, you know, just even minor, um, experiences that we have during the, the second half of the cycle to a whole, you know, host of combination of things where you're feeling a little bit sad and you, you've got, you [00:54:00] know, food cravings and you've got, um, whatever.

Um, but PMDD is, is more serious. It's generally like one of the defining characteristics of PMDD that separates it from, uh, from just run of the mill PMS is, um, is suicidal ideation. Mm-hmm. Um, so, and it's, it's funny because it is a real land, it's, it's a landmine for doctors to screen for PMDD because as soon as you ask somebody about p uh, about, um, suicidal ideation, there's a whole protocol that you have to follow.

Yeah. That could lead to institutionalization of their patients. And most doctors don't want to do that, um, for a good reason because the women don't want to do that. Yeah. Yeah. And so it's like, it's really, it can be a little bit tricky to navigate, but it's also, um, characterized by really debilitating, um, mood related symptoms.

Um, the sort of crown and jewel, um, symptomology of PMDD is, is are these really severe, debilitating mood related symptoms oftentimes, um, accompanied by suicidal ideation. And, um, you know, it's funny, so in my book, I, I list what the [00:55:00] criteria are for being diagnosed with PMDD. I don't actually publish 'cause there's a, uh, the DSM, the DSM guides, which, um, is a diagnostic statistical manual, which is what the a PA uses to define different categories of psychological illness.

Um, I can't, I can't publish exact questionnaire, but all of the items are in there. Yeah. They're in a table about what you need to be paying attention to and how clinicians are able to actually distinguish whether you fall into the category of PMDD or not. And, um, but it, it is really debil these debilitating mood related symptoms.

Mm-hmm. Um, and for women who have PMDD, I mean, this is like endometriosis, which was something we spent a lot of time, um, talking about last night at our really wonderful dinner with experts. And when you

hang out with endometriosis surgeons Yeah. Is what talked about. Yeah. It

was so, like there was scans being cast around the table.

It was just,

I was saying that I was like, at some point, always in our dinner, here comes the imaging and we started talking about cases and stuff.

So Fun. No, it was just, it was just so fun. So, um, but it, it usually takes women a [00:56:00] very long time to get A-P-M-D-D diagnosis. And so this is something that, um, I always recommend that women start tracking their symptomology early.

Yeah. Because if they can go to their doctor with evidence, um, and that's, this is what your doctor's going to ask for is like at least two months of evidence. Mm-hmm. Showing that your mood changes that you're getting that are so debilitating are. Specific to the luteal phase. Um, and this is something that is incredibly debilitating to women.

Yeah. I mean, it's incredibly debilitating. I mean, some women don't, aren't able to get outta bed. They lash out at people they love, and then they've got this brain because during the luteal phase, it's really primed for, um, social sensitivity to threats. And so they're lashing out at people and then they're really sensitive to the feedback they're getting.

And I mean, it just creates these loops that are really terrible for women. It's a really heartbreaking diagnosis to get, because as you noted, this is a woman feeling on the brink 50% of the time. Mm-hmm. It's a really terrible, it's a really terrible condition.

We're gonna talk about treatments. Uh, I don't wanna jump there yet, but, [00:57:00] uh, so I didn't know I had PMDD as a teenager and now I, I didn't know I had PMDD and I didn't know I had endometriosis and my doctors could care less.

Because they were like, take the pill. But I remember, um, being on the pill and being so debilitated that I would get in the shower and I would just cry and be on the floor of the shower, physically unable to get out. And I look back at that and I just remember thinking like, why, like, what's wrong with me?