Cortisol, the primary stress hormone released when your body perceives a threat, is essential for survival. In small doses, cortisol1 has beneficial effects, like waking you up in the morning, supporting energy, and helping the body deal with stress.

The problem is that high cortisol levels over a prolonged period can lead to adverse health consequences, both physically and mentally. Hormone imbalance, weight gain, and blood sugar imbalance are just a few of the physical effects of too much stress2 and elevated cortisol. But cortisol also plays a huge role in brain health, from mood and memory to learning and decision-making.

In fact, the connection between cortisol and cognitive function3 is so strong that chronic stress and high cortisol levels have been linked to cognitive decline and dementia. This makes sense because cortisol crosses the blood-brain barrier4 and binds to various receptors in your brain, especially areas that control memory, learning, and emotional processing.

In this article:

Let's take a closer look at how cortisol affects the brain, signs your brain is struggling, and what you can do to keep your cortisol levels in check.

What Gland Produces Cortisol?

Cortisol5 is produced by the adrenal glands that sit on top of the kidneys. The adrenal glands produce various hormones, including cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline. These hormones are essential for regulating the body's stress response.

The release of cortisol is controlled by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal6 (HPA) axis. This complex system starts in the brain and involves several different hormones.

Adrenal Gland Health

The HPA axis is activated in times of stress, triggering the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands. Cortisol then works to help the body cope with the stressor. Once the stressor is gone, the HPA axis should return to its normal state.

However, for some people, the HPA axis becomes dysregulated7, and cortisol levels remain high even when there is no longer a stressor. HPA axis dysregulation is what is often called adrenal fatigue in conversation. While it's not exactly correct to say the adrenals are fatigued, it is a common language used by patients who are trying to explain the symptoms they experience when the whole HPA axis system is thrown off.

Nourishing the adrenals (which we will discuss later in the article) can support a healthy stress response, lowering how much cortisol your brain is exposed to daily.

Signs That Your Brain is Struggling

The tricky thing about brain-related changes is that they don't always present themselves in obvious ways. It's not like a broken bone, where you can see the physical damage, and it's evident that something is wrong.

Cognitive decline, dementia, and brain fog often manifest as subtle changes in behavior or thinking patterns. For example, you might notice that you're having more trouble remembering names or where you put things. Or maybe you're feeling more forgetful than usual and having difficulty concentrating.

Brain fog isn't an actual medical diagnosis, but that doesn't make it any less serious and it can manifest in many ways.

Symptoms of Brain Fog

- Difficulty concentrating

- Trouble remembering things

- Feeling forgetful

- Poor decision-making

- Trouble multitasking

- Brain fatigue (feeling brain-tired but not necessarily body-tired)

How Can Cortisol Affect Brain Health?

The science behind how cortisol affects the brain shouldn't be ignored (and adverse outcomes can start younger than you think).

First, it's worth noting that occasional situational stress, like a work deadline or giving a presentation, doesn't have the same effect on the brain as chronic stress. Brief surges of stress can actually improve your performance and keep you more alert in these situations. It's only when cortisol levels stay elevated for extended periods that problems can occur.

But here's what we know: changes in the function of the HPA axis8 and consistently high cortisol levels are linked to an increased risk for brain-related disorders like dementia9 and Alzheimer's10.

This has been repeated in various studies11 that link high cortisol with brain-related issues for people without dementia like:

- Poor cognitive function

- Memory issues

- Language

- Spatial memory

- Processing time

- Social cognition

- Faster cognitive decline

A study12 following a famous cohort called the Framington Heart Study found that higher cortisol levels (especially for women) were linked to poor performance in memory, organization, visual perception, and attention. The study comprised over 2000 participants, primarily in their 40s. Those with higher cortisol levels also were associated with physical alterations to the brain linked to dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

Several other studies13 have noted that cortisol impacts brain volume in regions known to affect cognition, including gray matter, which is vital for processing information, and the hippocampus, which is essential for memory (stay tuned for more on why the hippocampus is so important).

What Does the Hippocampus Do?

The Hippocampus is a seahorse-shaped region in the brain that's important for learning and memory. It's located in the temporal lobe, just behind the ear. The hippocampus14 has a significant amount of cortisol receptors, which makes it especially vulnerable to the effects of stress.

Hippocampus-Dependent Learning and Memory

The hippocampus is essential for forming new memories and recalling old ones. It's also involved in navigation, spatial memory15, and declarative memory16, the kind of memory we use to remember facts and events.

This part of the brain is constantly active, even when we're not consciously thinking about memories. It's continuously encoding new information and making connections between different memories.

Hippocampus and the Stress Hormone Cortisol

High cortisol appears to significantly impact the hippocampus, to the point where very high cortisol levels may cause atrophy (shrinkage) of the hippocampus17.

Here's where it gets complicated—you learned the HPA axis regulates the stress response, but the hippocampus can also inhibit the HPA axis18. So when the hippocampus is impaired by stress19, it can worsen the stress response. This dangerous cycle can further damage the hippocampus and cause even more stress.

Studies have found that both directly administering hydrocortisone20, a synthetic form of cortisol, and exposing healthy younger subjects to stressors21 that increase cortisol negatively impacts working memory. Chronic stress may also accelerate apoptosis22 (cell death) in the hippocampus, although this was seen only in animal studies.

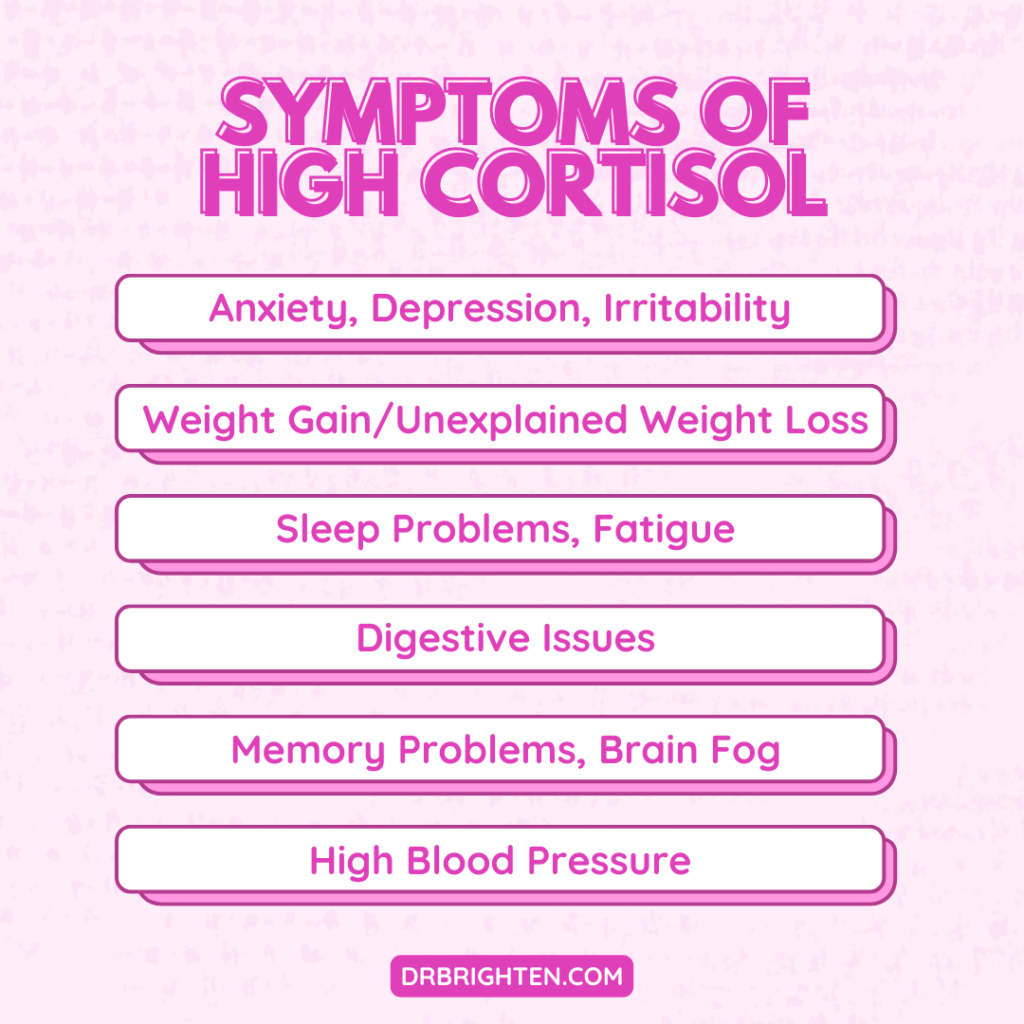

Signs and Symptoms of High Cortisol Levels

Clearly, stress isn't good for the brain or the hippocampus. So what signs should you watch for that may indicate you have high cortisol levels? Here are some of the most common signs and symptoms:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Irritability

- Fatigue

- Muscle weakness

- Weight gain or unexplained weight loss

- Skin problems, such as thinning skin, easy bruising, and stretch marks

- Digestive issues, such as diarrhea, constipation, and nausea

- Sleep problems, such as insomnia and night sweats

- High blood pressure

- Headaches

- Memory problems

- Cloudy thinking or “brain fog”

Stress can look different for each person, and we all have different thresholds for stress. You may be able to handle a lot of stress before it starts to impact your health, while someone else may begin to feel the effects of stress at much lower levels. Take a closer look at how stress affects you mentally and physically, and pay attention to any changes that may indicate high cortisol levels.

How to Lower Cortisol Levels and Improve Adrenal Function

Nutrition, lifestyle, and supplements are my go-to approach for supporting adrenal health and lowering cortisol levels. Here are some of the best things you can do to protect your brain from the harmful effects of stress.

Foods that Lower Cortisol

Insulin resistance23 and inflammation are closely tied to brain health. Diet patterns like the Mediterranean or Mind Diet24 have been shown to help protect cognitive function and reduce the risk of dementia. These diets are full of nourishing anti-inflammatory foods like fruits, vegetables, olive oil, fish, and nuts. You’ll find these types of foods in our free hormone balancing recipe guide and meal plan.

High cortisol also increases blood sugar levels, so eating to support stable blood sugar can help. This means eating regularly spaced meals and including protein, healthy fats, and fiber at every meal.

And of course, you can't forget about your gut health. The gut-brain axis is a two-way street, meaning that what's going on in your gut can affect your brain and vice versa. So a healthy microbiome may influence your stress response and brain health25.

Supplements to Lower Cortisol

- Adaptogenic Herbs. Adaptogenic herbs help the body adapt to stress and normalize cortisol26 levels gently yet effectively. Some of my favorite adaptogens for lowering cortisol include ashwagandha27, Rhodiola, shavarti (asparagus racemosus) and holy basil.

- Magnesium. Magnesium is a mineral involved in over 300 functions in the body, including the stress response. Low magnesium28 may exacerbate stress, but stress can also increase magnesium losses.

- Vitamin C. Vitamin C is a powerful antioxidant that helps protect the body from stress. In one study29, people who took a vitamin C supplement had lower cortisol levels and blood pressure.

- B-Complex Vitamins. B vitamins contribute to the enzymatic reactions30 involved in the stress response. Taking a B complex31 could help improve the impact of stress on your body.

- Phosphatidylserine. Phosphatidylserine32 is a type of fat found in cells, including those in your brain. It's vital for brain health and cognitive function33. Phosphatidylserine has also been shown to lower cortisol levels34 and improve the stress response.

I've created a comprehensive, all-in-one Optimal Adrenal Kit that includes all these essential nutrients, botanicals, and more to support optimal stress and hormone balance in the body.

Lifestyle

Stress resilience takes a whole-person approach, so in addition to diet and supplements, lifestyle habits can also make a difference in your stress resilience and adrenal health (and just make you feel better from the inside out).

- Exercise. Exercise is one of the most effective ways to lower cortisol levels. Not only does it help mitigate stress35, but it also boosts endorphins, which are hormones that have mood-elevating effects.

The tricky thing is to not overdo it, as over-training can exacerbate cortisol. So, mix in a few rest days to stretch too.

- Meditation. Meditation is a mindfulness practice that helps you focus on the present moment and let go of stress. Research36 shows that meditation can help lower cortisol levels and improve the stress response.

If you're brand new to meditation, it can feel a little intimidating, but there are plenty of apps and free resources to get you started.

- Sleep. Getting enough sleep is essential for adrenal health. Poor sleep37 interferes with the normal function of the HPA axis, impacting stress, adrenal health, and so much more.

I won't pretend that sleep struggles are an easy fix. All of the above tips for the adrenals are also important for adequate rest. Also, ensuring you have a quiet, cool sleep environment with a calming bedtime routine can help. You can read more sleep tips in this article.

Take Steps Now to Limit the Effect of Stress on Your Brain

Sometimes reading these articles can sound a little scary, especially if stress is a significant factor in your life. But my hope is that you can take this information and use it as motivation to make a few changes.

Small steps can add up, even if it's one or two changes to get you started. Supplements, nutrition, and lifestyle-focused habits like sleep and stress are all essential for managing stress.

If you need extra support, you can check out my free Hormone Balancing Starter Kit, which includes a 7-day plan and recipe guide to help you feel confident as you start your journey.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5137920/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5573220/ ↩︎

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0009898113001484?via%3Dihub ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860380/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7364861/ ↩︎

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2019.00043/full ↩︎

- https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/REVNEURO.1999.10.2.117/html ↩︎

- https://n.neurology.org/content/88/4/371 ↩︎

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2019.00043/full ↩︎

- https://n.neurology.org/content/91/21/e1961 ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5619133/ ↩︎

- https://academic.oup.com/edrv/article-abstract/12/2/118/2548633 ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1815289/ ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11718892/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4462413/ ↩︎

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2019.00043/full ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3527687/ ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10443770/ ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17035163/ ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15950198/ ↩︎

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2019.00788/full ↩︎

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-04258-9 ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24062644/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3573577/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3573577/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7761127/ ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11862365/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6770181/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6770181/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4258547/ ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25933483/ ↩︎

- https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/125593 ↩︎

- https://journals.lww.com/acsm-healthfitness/fulltext/2013/05000/stress_relief__the_role_of_exercise_in_stress.6.aspx.%C2%A0 ↩︎

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23724462/ ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688585/ ↩︎